Articles

About the genre and technique of the poster

Written by Tibor Szántó. This piece was originally published in Szántó's 1986 book, titled The Hungarian Poster. Translation by Anna Somos with a few minor alterations from the original.

The oldest relics of marketing were discovered amidst the ruins of Pompey excavated in 1711. Craftsmen’s workshops were indicated by red paint or texts engraved into tables of stone placed on the walls. Boards at the forums informed ancient citizens about tournaments or theatre plays. In the subsequent centuries guesthouses and workshops were marked by signs engraved in stone or painted on wood. From the time of the 13th century and on, signboards carved in statues, forged iron and later board paintings are preserved. These signboards did not only indicate the name of the guesthouse, the tradesman or the craftsman, but often the streets as well, where the masters worked. This frequently was the way street names were born, many of which survived centuries of changes in society. (For example the street of Gold makers in Prague or Soap makers in Cluj-Napoca).

Signs and boards with texts were the means of competition, and were made increasingly ornamental, big and characteristic over time by the engravers or painters. In Paris in the 17th century an order limited the size of signs. (The size of urban commercial platforms are still limited by regulations today). Significant painters of the 18th century did not consider themselves above dedicating their art to publicity and commerce. Museums in Paris have numerous decorative painted signs by Watteau, Chardin, Prud’hon and Géricault. The Budapest History Museum also has a number of painted signs created by Hungarian classicist masters.

The earliest printed posters occurred on the walls in the form of woodcut leaflets, later as sheets printed with typographic tools (in some cases decorated with woodcut images). In 1517 Martin Luther posted his Ninety-Five Theses on the door of the Wittenberg Church. At that time, this was the modern way of propaganda in the ideological and political battles. The print and poster archives of our libraries contain thousands of printed materials which used to spread news, events or orders of political fights, revolutions and counter revolutions for centuries in history.

In 1797 the invention of Alois Senefelder from Prague – lithography – established a new form of advertising. In the second half of the 19th century posters produced with lithography replaced signs, displays or typographic posters on the streets of big cities.

This then new and soon to become very diverse art form was developed by the competitive spirit of capitalism to a novel type of imagery. Poster has become the visual means of commerce, industry, culture and political agitation, capable of making a direct impression.

Our website presents the formation, variety of styles and evolution of Hungarian poster art (the most important branch of applied graphic design). However, the history of Hungarian poster art doesn’t only document the inception and development of this unique graphic design form, but it also chronicles the political battles, changes and events of Hungarian industry, commerce and cultural life of the past century, through the language of reproduced imagery.

The technique that enabled the reproduction of the masters’ work was lithography, the Czech actor, Alois Senefelder’s invention. Senefelder was copying sheet music for some extra income when he started wondering how it’d be possible to produce copies of one original piece by a cheaper and mechanical method instead of the costly metal plates and the exhausting manual transcription work.

Besides the traditional method of sheet music engraved into metal plates, the technique of manual typesetting, letterpress printing was regularly applied for sheet music after book printing became widespread. Miklós Tótfalusi Kis used typeset sheet music in his small book of psalms. Emauel Breitkopf, German typographer perfected the technique of typeset sheet music in the 18th century but it was still slow and expensive. Senefelder’s invention, lithography enabled a new way of printing sheet music that was faster and cheaper than the former ones. The new technique was initially used only for simple prints and sheet music. Later – when fine artists discovered the potential lithography held – the high volume reproduction of posters and artworks requiring colour printing had begun.

From the second half of the 19th century and the turn of the 20th century, after Chéret, Toulouse-Lautrec, Steinlen and others, posters with an artistic quality, printed with the new technique occurred on the advertising columns.

Lithography also created the opportunity of reproducing paintings and colourful codices which were only available in museums in previous times. Besides, the new technique provided almost unlimited possibilities for the masters of reproduced graphic design.

Senefelder’s invention democratized art.

Besides artistic prints, reproductions and book illustrations, occasionally complete books could be printed with the new technique. Alluring, sometimes colour deluxe books were published, often illustrated by esteemed artists of the era. Lithography appeared in journals, and was used for illustrations of literary works and fashion columns. The caricatures published in political papers and comic books criticizing adverse social issues even had a society shaping power.

The cliché in case of intaglio printing (chalcography, etching, etc.) is the surface sunken into the plate, while in case of letterpress printing (manual setting, mechanical setting, wood engraving, steel cliché) it is raised from the flat surface.

The cliché in lithography - later called planographic printing technique and at a later stage of technological development offset printing – instead of using the sunken or raised surfaces, used the text and the image lithographed onto the polished surface of limestone. The surface of the polished limestone behaves as a capillary and is capable of restraining water. If an image is painted on this surface with oil-based paint, and is rolled over with a dampening roller, the limestone repels the water in the areas “sealed” with the image, instead of absorbing it. Afterwards, if the limestone meets with the oily printing ink, the parts not for printing on the stone previously dampened with water will repel the oily ink.

The lithographic stone is porous limestone. The stones most suitable for lithography were mined in Solnhofen in Bavaria. The stones were cut into 5-10 cm thick blocks and were polished. The stones could be reused by polishing again the surface.

The lithography crayon used by the artists is a solid mixture of soot, stearin, soap, turpentine and crayon. To produce line drawings, the artists used tusche with chemical ingredients similar to crayon. The inverse image was drawn onto the limestone with the greasy crayon (or tusche). In order to avoid the lines blurring of the drawn image, the surface of the stone is acidified with nitric acid. This penetrates to the pores of the limestone, thus water cannot leak into the capillaries but remains on the surface, what makes the non-image parts of the surface repelling to the printing ink.

Chromolitography is a process used for making multi-colour prints. The preparation of the printing surface starts with making contour images of the original one on a special paper. Then the images are pressed onto multiple lithographic stones of the same size, one for each colour that is required for the final result. Then the cliché of each colour is prepared according to the contours; the full toned parts are drawn with tusche while the different hues are produced with crayon, pen, dotting or spraying techniques. When determining the colours, the chromolitographic experts’ sense of colour is substantial. Finally, the knowledge and expertise of the lithography artists determine how the subtle shades of the image unfold from the layers of colours pressed onto each other.

In order to make sure that the image is perfectly transferred to the paper tightened over the cylinder, the cylinder is covered with a rubber blanket, which first rolls against the inked plate, thus the image is transferred to the rubber from the limestone. Then the paper passes between the blanket cylinder and the plate, receiving pressure from both sides. According to the observations, the print transferred to the paper from the rubber blanket is more perfect and cleaner than the one from the stone.

This experience is what developed offset printing which involves a separate rubber roll that takes the ink directly from the plate, thus the paper is not pressed against the plate but only against the rubber roll. Later the plates made of aluminium or zinc (instead of stone) were tightened over hollow cylinders. The new printing technique facilitated the production of mechanical constructions that replaced heavy limestone plates, what enabled the production of greater number of copies produced by faster machines (today 15 000 per hour). Another advantage of the new method is that it can be used even with papers with rougher surface.

Manual lithography was later replaced by a newer technique of offset colour printing. The printing plates in this case are made with the raster (broken down to points) diapositive films of the image separated into the four colours. The differences of hues occurring during the process are fixed by manual retouch. Nowadays the colour separation is done by electronic laser beam machines. The images are copied to the printing plates by mechanical equipment.

In case of offset printing, the rasterpositive image is transferred onto the plate true to the original. This pressing plate is placed on the rubber blanket with the reversed image, transferring the true image onto the paper.

The modern machines can produce simultaneously two, four or even six colours. There are multiple colour printing rotary offset machines as well that can print on endless paper rolls.

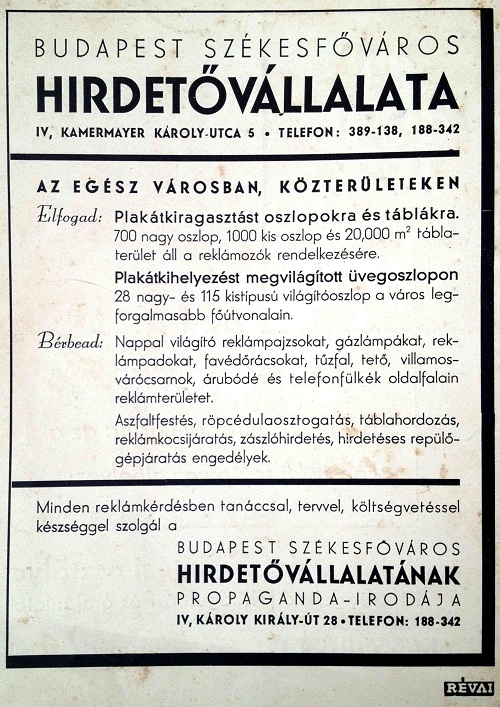

Capital City Advertising Company advertisement 1938