Description:

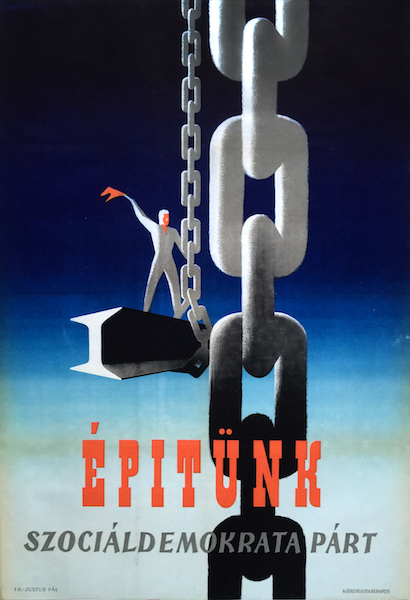

Zoltán Tamássi's outstanding political poster for the 1947 elections in Hungary is one of the greatest examples of propaganda art ever created. It carries the message that the rebuilding of the country, devastated after World War 2 is of utmost importance for the Hungarian Social Democratic Party.

The symbol of this message is a messenger, standing on a steel beam which hangs from a crane chain in infinite space. He's right arm is in the air, waving a red kerchief. The same red colour is used for the simple, one word slogan of the poster "We build" ("Építünk" in Hungarian). Beneath the slogan, we can find the name of the Social Democratic Party.

The artist, Tamássi was famous for his ability to design well-polished, concise symbols that were able to transmit extremely compressed, but clear messages, and this is one of his best, most important works.

The Hungarian parliamentary election of 1947, which later became infamously the "blue-ballot" elections, were held on 31 August 1947.

The Hungarian Communist Party, which had lost the previous election, consolidated its power in the interim using salami tactics. This fact, combined with the weakening of the opposition and a revised electoral law, led to further Communist gains. It was Hungary's last remotely competitive election before 1990.

In the summer of 1947, in the presence of Soviet arms, Hungary prepared for a new election. The Communists intended to exploit the situation that arose as a result of the disarray of their main rival, the Independent Smallholders Party, to gain a clear majority in the legislature. Their campaign's central theme was the party's national character; during the coalition years, the Communists had presented themselves as the champion of national interests and as heirs to the nation's tradition. During these preparations, two events clearly indicated the politicisation of economic issues and the economic significance of political decisions. Upon pressure from Moscow, on 10 July the Hungarian government announced its abstention from the conference that was discussing the Marshall Plan for Europe's postwar reconstruction, which, as Joseph Stalin realised, was an attempt of the United States to counter the Soviet military and political dominance of central and southeastern Europe by economic machinations. Slightly earlier, a State Planning Office was created, the three-year plan as urged by the Communists in the previous year was enacted, and on 1 August its implementation began.

It was after these further steps away from the Western democracies and towards a Soviet-type system that elections were held. They took place on the basis of a new electoral law, which excluded about 466,000 people (almost a tenth of the electorate) from the vote on grounds of membership in the pre-war fascist party; more parties participated, with only fascist ones still prohibited. In order to further guarantee success, the Communists severely rigged the elections (50,000 fraudulent votes were cast for them) but nevertheless managed to increase their vote share to a mere 22%, and failed to attain an absolute majority even with the other parties of the Left Wing Bloc. Though the emasculated and demoralised Smallholders only scored 15%, the groups that had seceded from them did well: the Democratic People's Party of István Barankovics came in second (keeping alive a real opposition and showing the strength of popular commitment to pluralism), and Zoltán Pfeiffer's Independence Party did not lag far behind the Social Democrats.

However, the Smallholders' left wing thwarted a coalition initiative from the two main opposition parties, and the old coalition remained. The manageable Smallholder Lajos Dinnyés remained as Prime Minister, and dutiful fellow travelers from the other parties were named to the cabinet for the sake of preserving the parliamentary facade. Even this turned out to be completely redundant very soon thereafter, with the gradualist approach abandoned and salami tactics accelerated. The Cominform came into being just days after the new Dinnyés government was formed. In December, Dinnyés himself was replaced by the leader of the Smallholders' left wing, the openly pro-Communist István Dobi. Intimidation, targeting of the increasingly submissive democratic parties (and absorption of the Social Democrats), nationalisation, collectivisation and other measures soon rendered the period 1945–47 a short democratic interlude, and the coalition became a mere memory a year and a half later, with the Communists wielding exclusive power.

(source: wikipedia.org)

Zoltán Tamássi was an important poster artist and graphic designer.

His master was Ferenc Helbing at the Applied Art School of Budapest, from where he graduated in 1934. Besides being an artist, he was also good at sports and was a professional soccer player playing in a famous Hungarian soccer team, FRADI (aka. Ferencváros or FTC). In 1933 the team won the national championship, however Tamássi got chance to prove his talent only three times during the season. Being a multi-talent, he was also known as ski jumper and race car driver. The love of sport was present through more generations of his family.

In 1937 together with György Konecsni he designed the Hungarian Pavilon of the Paris World Exhibition. After 1945 he became acknowledged as a graphic designer thanks for his political posters (between 1945-49) and safety campaign posters. Between 1970-1981 he was teaching graphic design at the University of Fine Arts, however, before 1947, he worked as a sports trainer as well,

Between 1945 and 1946 he worked at a State Bureau of Propaganda. In 1945 Tamássi was one of the leading graphic artists who manage to reform the visual language of the political poster in Hungary. He designed election campaign posters for opposite parties. Initially he was the propagandist of the Peasants’ Party but later on he got commissioned by the the Social Democratic Party and the Hungarian Communist Party. His works are defined by his keen sense for creating clear and monumental compositions. He used sculpture-like, massive shapes, usually setting an endless space as background. His characters often represent a particular social class: the worker, the peasant, the intelligentsia; or the enemy: the fascist or imperialist bourgeois. He preferred to use interesting or unusual angles, view from above and below in order to obtain a dramatic effect. Tamássi often applied well-known symbols, like the broken shackles. His posters cover important topics of the age: democracy, rebuilding, distribution of land, etc.

After the political turn in 1949, Tamássi remained a successful poster designer. He mostly designed travel, safety and propaganda posters. Some of them was to raise the attention to the dangers of public transport. His designs are very modern, clear compositions, presented by a very effective and powerful visual language.